A Postcard View of History: Tribute to Minnie E. Brooke

When Chevy Chase resident, Minnehaha “Minnie” Etheridge Brooke, set out to achieve something, she did it with verve and passion. For many years she worked as a suffrage speaker, touring cities around the country to organize street meetings for women’s rights. In 1913, she also helped to organize the first Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC. For many years thereafter she spent Saturday nights at the Benjamin Franklin statue on Pennsylvania Avenue, convincing bystanders that women deserved the right to vote. She had a successful career as a restaurateur, managing the Cosmos Club and numerous tea houses, before opening her own establishment, Brooke Farm Tea House, on the “No Gain” estate between Taylor and Thornapple Streets on the Maryland side of the border. For a while, she also ran an inn from this home.

When Chevy Chase resident, Minnehaha “Minnie” Etheridge Brooke, set out to achieve something, she did it with verve and passion. For many years she worked as a suffrage speaker, touring cities around the country to organize street meetings for women’s rights. In 1913, she also helped to organize the first Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC. For many years thereafter she spent Saturday nights at the Benjamin Franklin statue on Pennsylvania Avenue, convincing bystanders that women deserved the right to vote. She had a successful career as a restaurateur, managing the Cosmos Club and numerous tea houses, before opening her own establishment, Brooke Farm Tea House, on the “No Gain” estate between Taylor and Thornapple Streets on the Maryland side of the border. For a while, she also ran an inn from this home.

Brooke used this tea shop to promote her political agenda, hosting national guest lecturers, meetings of the Chevy Chase Woman’s Club and, after enfranchisement, luncheons for the Women’s Democratic Club of Montgomery County. Although she never had children of her own, Brooke became a Girl Scout Leader, serving as a Captain to inspire the next generation of girls.

Minnie E. Brooke was a business entrepreneur who tried to capitalize on a new craze sweeping the county—sending postcards through the US mail. Although the exact dates are uncertain, Brooke published hundreds of postcards with images of sites throughout Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia from about 1900 until 1913.  It is not known if Brooke took any of the photographs herself, but most likely she purchased the negatives from a few professional photographers who gave her the rights to reproduce the images under her name. As her enterprise of selling postal mementos grew, the cards traveled all over the county and, indeed, the world. By 1918, according to the Boyd’s city directory, she was proprietor of The Brooke Shop, at 730 15th St, NW, a store where tourists could purchase souvenirs. This successful venture earned her the reputation for being one of Washington’s most prominent businesswomen. By the late 1920s, she and her husband, a florist named Wentworth, sold their Chevy Chase tea house and inn, and moved from Thornapple to 210 Raymond Street (presently number 3616) in Section Three, a few blocks away. A few years later she moved to Takoma Park where she died on February 8, 1938, in her early sixties, and was buried at the Rock Creek Cemetery. For someone who lived such a purpose-driven life, it is somewhat ironic that Brooke, unintentionally, created this photographic record of the DC area during the early 1900s, making herself a photo documentarian for her period. We are gratefully indebted to her for capturing so many of the wonderful images which appear in this presentation.

It is not known if Brooke took any of the photographs herself, but most likely she purchased the negatives from a few professional photographers who gave her the rights to reproduce the images under her name. As her enterprise of selling postal mementos grew, the cards traveled all over the county and, indeed, the world. By 1918, according to the Boyd’s city directory, she was proprietor of The Brooke Shop, at 730 15th St, NW, a store where tourists could purchase souvenirs. This successful venture earned her the reputation for being one of Washington’s most prominent businesswomen. By the late 1920s, she and her husband, a florist named Wentworth, sold their Chevy Chase tea house and inn, and moved from Thornapple to 210 Raymond Street (presently number 3616) in Section Three, a few blocks away. A few years later she moved to Takoma Park where she died on February 8, 1938, in her early sixties, and was buried at the Rock Creek Cemetery. For someone who lived such a purpose-driven life, it is somewhat ironic that Brooke, unintentionally, created this photographic record of the DC area during the early 1900s, making herself a photo documentarian for her period. We are gratefully indebted to her for capturing so many of the wonderful images which appear in this presentation.

Postcards Take Off in America

Brooke’s business of selling postcards was part of a larger trend of trying to democratize communication channels at the turn of the nineteenth century. Telephone service was expanding during the first decade of the nineteenth century, but making a long distance phone call was extremely expensive. Instead, tourists, new immigrants, lovers, and friends alike could buy a “penny postcard,” spending an additional penny to send it through the domestic mail and two cents internationally. We could compare these short, simple notes as the equivalent to our email today! The period from 1903 until 1913 saw an explosion in the postcard industry with the advent of Eastman Kodak’s postcard-sized development paper and the occurrence of several American expositions and fairs. Although the images people purchased were local, most of the postcards from this period were made overseas, especially in Germany, where manufacturing processes were the best. Sometimes European companies kept agents and offices in America, where people like Brooke could submit their original negatives and have hundreds of cards printed and shipped across the Atlantic, at a cheaper price and a better quality than what could be done domestically. However, the onslaught of World War I curbed German civilian manufacturing and made the delivery of anything by ship vulnerable to attack or confiscation. Brooke’s cards are consistent with this event, most having postmarks that predate the war.

Brooke’s business of selling postcards was part of a larger trend of trying to democratize communication channels at the turn of the nineteenth century. Telephone service was expanding during the first decade of the nineteenth century, but making a long distance phone call was extremely expensive. Instead, tourists, new immigrants, lovers, and friends alike could buy a “penny postcard,” spending an additional penny to send it through the domestic mail and two cents internationally. We could compare these short, simple notes as the equivalent to our email today! The period from 1903 until 1913 saw an explosion in the postcard industry with the advent of Eastman Kodak’s postcard-sized development paper and the occurrence of several American expositions and fairs. Although the images people purchased were local, most of the postcards from this period were made overseas, especially in Germany, where manufacturing processes were the best. Sometimes European companies kept agents and offices in America, where people like Brooke could submit their original negatives and have hundreds of cards printed and shipped across the Atlantic, at a cheaper price and a better quality than what could be done domestically. However, the onslaught of World War I curbed German civilian manufacturing and made the delivery of anything by ship vulnerable to attack or confiscation. Brooke’s cards are consistent with this event, most having postmarks that predate the war.

About the Views

Most of the postcards that Brooke published of the DC area are called “views,” meaning pictures of the city and its surroundings. Sometimes they were vast cityscapes, such as the building of Union Station; other times they were a small glimpse into the life of its residents, such as people feeding geese at Rock Creek Park. Not only do her images preserve the look of public monuments and buildings from the early 1900s, but also the interior spaces of buildings, such as the YMCA in downtown DC, or Union Station. We can see how people decorated their rooms, what they wore, and how technologies like electricity, phones, and piped water were used in the early 1900s. By studying the details in these images, historians can learn about the curve of a road, the placement of a traffic light, travel in snowfall, or how people spent their time waiting for a train. Sometimes “view” postcards were made and published using REAL photographs. These “Real Photo” postcards are very rare, because usually they were taken by itinerant photographers who produced only a small quantity and then pasted a postal logo on the back for sending. Such images are invaluable to historians. For example, in 2005, two local postcard collectors, Joseph V. Valachovic and Harold V. Silver, opened their private collections to the CCHS and unearthed two never-before-seen pictures of Chevy Chase Lake.

Most of the postcards that Brooke published of the DC area are called “views,” meaning pictures of the city and its surroundings. Sometimes they were vast cityscapes, such as the building of Union Station; other times they were a small glimpse into the life of its residents, such as people feeding geese at Rock Creek Park. Not only do her images preserve the look of public monuments and buildings from the early 1900s, but also the interior spaces of buildings, such as the YMCA in downtown DC, or Union Station. We can see how people decorated their rooms, what they wore, and how technologies like electricity, phones, and piped water were used in the early 1900s. By studying the details in these images, historians can learn about the curve of a road, the placement of a traffic light, travel in snowfall, or how people spent their time waiting for a train. Sometimes “view” postcards were made and published using REAL photographs. These “Real Photo” postcards are very rare, because usually they were taken by itinerant photographers who produced only a small quantity and then pasted a postal logo on the back for sending. Such images are invaluable to historians. For example, in 2005, two local postcard collectors, Joseph V. Valachovic and Harold V. Silver, opened their private collections to the CCHS and unearthed two never-before-seen pictures of Chevy Chase Lake.

Documenting Chevy Chase

To our knowledge, Brooke published only seven scenes of Chevy Chase, MD. All of them were taken between 1900 and 1910. Reproductions of Postcards Courtesy of Joseph J. Valachovic and Harold V. Silver.

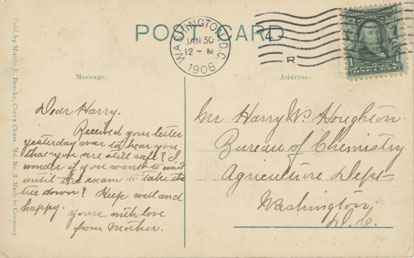

What the Back of a Postcard Tell Us

The backside of a postcard reveals a lot of information about how to date the image on the front. Sometimes a postmark will give an approximate age, but if the postcard has not been mailed, look for what is called an undivided back. Up until 1906, senders could only write on the front of the postcard and print the address on the back. After Congress passed an act instituting a divided back in 1907, both addresses and messages appeared on the same side. Since almost all of Brooke’s postcards have the divided back, we can tell that she published these after 1907. Don’t forget to read the message on the front or back of a postcard—sometimes there are interesting stories revealed. Image of Backside of Minnie Brooke Postcard courtesy of Harold V. Silver

Kids You Too Can Be a Historian!

Minnie Brooke started her business selling postcards to make money, but she also documented life in the early 1900s. Because the camera became a widely affordable technology, more and more people living during her time could snap pictures and record their world. Postcards are just one of many resources for those wanting to learn more about the past. What technologies do you have available, in addition to the camera, to help you record history? How can you use a computer, camcorder, and even an iPod to record pictures, words, and sounds from the present, preserving information about you and your community for a future generation? Postcards have been around for hundreds of years and still serve the same purpose—to send a brief note in the mail. Now we have the Internet to send messages even quicker, but the postcards that you send on your next vacation will still tell a story to people living in the future if they are saved. What do you want people reading your postcard 50 or 100 years from now to know about yourself, your likes and dislikes, your hobbies, your school, your family, your town, what you want to be when you become an adult? Be inspired by Minnie Brooke and become a historian yourself!

Be inspired by Minnie E. Brooke—Donate copies of your pictures to the CCHS!

Know more about Minnie E. Brooke? Please contact us at the CCHS.

©2006 Written by Evelyn Gerson for the Chevy Chase Historical Society.