of Robert Donnelly and used with

his permission.

Harry M. Martin and Martin's Additions

Harry Martin? Oh, I was a little boy at the time. I remember, I have a vision of him. He was heavyset, had red hair, a red moustache, but he was very much of a go-getter and businessman. - George Winchester Stone, Jr., whose family moved to Cummings Lane in Martin’s Third Addition in 1909.

Harry M. Martin (1865-1956)

Harry Martin played a key role in the suburbanization of Montgomery County, and the development of his “Additions to Chevy Chase” were part of the changes that transformed a small farm lane into the modern residential street called Cummings Lane.

Harry M. Martin was born in Washington, DC in 1865. He was one of eight children born to James Martin, a bookbinder, and his wife, Helen Marian Simpson. The Martin family moved from the District of Columbia to Kensington, Maryland sometime after the 1880s. Harry Martin lived in Montgomery County for most of his life, including several years at his new home on Cummings Lane. In his final years, he lived at a nursing home in Washington, DC.

Martin’s real estate career began in a company he owned with his brothers Tom and Lee Roy in the 1890s. At the time Harry Martin began buying farmland in Chevy Chase, H. M. Martin and Co. was located at 1741 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, in Washington, DC. Between 1904 and 1906, he bought land that was once part of the “No Gain” plantation, and subdivided it into four sections, creating “Martin’s Additions to Chevy Chase.”

By marketing his new suburban subdivisions as “additions” to Chevy Chase, Martin took advantage of all the amenities and name recognition the Chevy Chase Land Company had created since the 1890s.

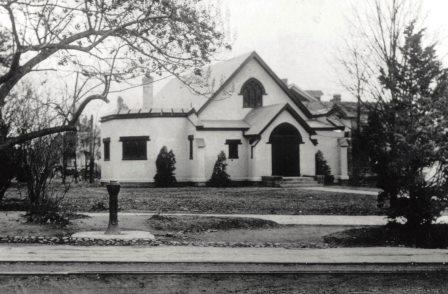

Martin also built a large house for himself on Cummings Lane, or Cedar Avenue as he named it on the subdivision plat for Martin’s Third Addition. As a new resident of his subdivision, he became involved with the local community. For example, members of a newly formed Presbyterian congregation met at his home in 1906. The following year, Martin helped them buy a lot for their church at Connecticut Avenue and Chevy Chase Parkway. His connection to the Presbyterian Church was strong, and he would later be one of the founders of the Warner Memorial Presbyterian Church in Kensington, MD.

In 1908, however, he sold his house in Martin’s Additions to the William Orme family, and he moved back to Kensington. He developed Chevy Chase View, which later became part of Kensington, as well as new subdivisions in Germantown and along Norbeck Road. He was well-known to others in his field, and frequently consulted for his “keen sense of real estate values,” according to his grand nephew, Robert Donnelly.

In July 2013, Mr. Donnelly wrote the following about his great uncle:

Harry was thoroughly involved in civic affairs. He was the prime organizer of the Chevy Chase View Special Taxing District. After having served ad interim as a committeeman, Harry was elected the first Chairman of the Citizens Committee in 1925, and served the Committee until 1938. His public spirit was such that in one case he signed a petition against the establishment of smaller lot sizes despite the fact that such a change would have been to his financial advantage. In one history of Montgomery County, Harry is noted for “leading” Kensington residents in a demand for a high school in their community.

Harry never married but took custody of his two nephews, Lawrence and George Smoot and oversaw their growing up. He provided a home at various times to members of his family including his sister, Katie, and her husband, Lars Erickson and, later, to his niece, Evelyn, and her children when they were between travels to be with her husband during WWII. Interestingly, Harry never learned to drive. He depended heavily on associates, friends and neighbors for transportation. He could often be seen at Connecticut Avenue and Dresden Street where he would hail down cars, get in and ask to be taken on his way! He was hard of hearing and very deliberately would turn off his hearing aid if a discussion was not proceeding to his liking. In many respects, Harry Martin was larger than life.

Harry M. Martin was my great uncle. I remember him as the patriarch of the family and, for me, a rather fearsome old gentleman. He was, however, putty in my mother’s hands.

Others had similar memories of Harry Martin. William Sharon Farr, President of the Chevy Chase Land Company from 1946 to 1972, remembered Mr. Martin in his 1986 oral history interview with CCHS. He was, Mr. Farr said, “full of ideas.”

Did you ever meet Mr. Martin? He was a character. He lived up in Kensington. But years before, he had started this subdivision over here called Martin’s Additions. And he also was involved in the little streetcar. As you would come out in the streetcar to Chevy Chase Lake, that was the end of the line. But there was another streetcar you would get onto and you would go out to Kensington. And he owned that. He had, I think, two streetcars. He had to have two because one of them was out of order most of the time! But he was really interesting. He used to come and see me when we had an office in town

Mr. Farr remembered that Martin was very upset about the Chevy Chase Lake dance pavilion in the 1930s. After Prohibition was repealed in 1933, the managers of the amusement park began serving beer, and Mr. Martin was very concerned that young people were drinking.

So Mr. Martin said, “All those young people. No beer, no beer.” And he really raised some smoke about it.

In addition to his real estate and civic concerns in Montgomery County, Harry Martin was active in Maryland politics. He also worked for Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt during their presidential campaigns. Under Wilson, he was appointed first assistant to the fuel administrator.

By the time of his death in 1956 at age 90, Harry Martin’s work as a developer set the stage for the postwar suburbanization of Montgomery County. In the rest of this section, we focus on his Third Addition to Chevy Chase – one of his first subdivisions, and the one that transformed Cummings Lane from a small country lane to a modern suburban street lined with single family homes.

Martin’s Third Addition

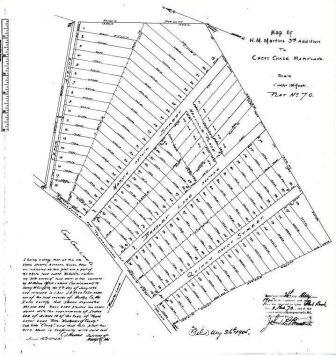

Cummings Lane was on the northern boundary of Harry Martin’s “Third Addition to Chevy Chase,” a tract of 35 ¼ acres which Martin purchased from Henry Griffith on August 26, 1905. Mr. Griffith was one of the heirs of the remaining property from the “No Gain” plantation. Formerly owned by John Hopkins Anderson, it had once been as large as 300 acres. Griffith and his wife, Isabella, also a “No Gain” heir, sold a few lots on the east side of Brookville road. Although some of the Anderson estate property was sold to the Chevy Chase Land Company (areas which are today known as Section 3 and Section 5), Lots No. 1 and 2, as shown in the land survey map below were sold to Harry Martin.

Cummings Lane and Cedar Avenue

Affordable Suburban Homes

Harry Martin offered lots in his new subdivision at significantly lower prices than those for sale by Chevy Chase Land Company. Deeds from the period show that Martin required the construction costs for new homes to be at least $1,750. By contrast, the Chevy Chase Land Company required houses on Connecticut Avenue to have a minimum construction cost of $5,000, and those built on side streets, $3,000. Martin worked with several local builders, including Horace Troth, Albert N. Prentiss, and John Reid. The neighborhood attracted middle-class federal employees, as it offered quality housing close to Washington, D.C.

A newspaper advertisement in The Evening Star, published on July 11, 1905, describes the lots in “Martin’s 3d Section” as 50 x 120 to 225 feet deep – 6,000 to 12,000 square feet. The list of amenities and selling points is long:

- Have finest car service; single fare.

- Beautiful situation.

- Fine views.

- Large trees.

- Good spring water.

- Everything that is desirable for attractive and pretty home, or good security in way of investment.

- Best terms on best land on the market.

- Your chance to get good land and decided bargain.

- Will build homes for purchasers at actual cost.

The street car line was at the top of the list, and with good reason. Few government workers owned automobiles at the turn of the century, so new residents would need public transportation. Taking advantage of the already existing streetcar line on Connecticut Avenue, Martin was able to claim that his lots had easy access to the trolley line. In practice, however, it was not so easy to get from the new homes on Cummings Lane to the streetcar on Connecticut Avenue.

In the early days, residents had to walk across fields, along paths that were often muddy. In 1906, residents of the area formed the Chevy Chase Home Association and at a cost of $14 for lumber, $2 for stone, and the donation of their own labor, they built a 350-foot path across the fields. It was one board wide. On winter work days, commuters from Harry Martin’s Additions hid their lanterns in the bushes near the trolley tracks on Connecticut, so they could follow the wooden pathway home in the dark hours at the end of the day.

Many Civil Servants Lived in Martin's Additions

These are just a few of the early residents of Martin's Additions who worked for the Federal Goverment -- and made the daily commute via the Connecticut Avenue streetcar:

Faith Bradford |

Library of Congress |

Agnes Cummings |

Treasury Department |

William Greeley |

Forestry Service |

Dr. Ruben Griggs |

Department of Agriculture |

Ferdinand Reichmuth |

United States Navy |

Dr. Vernon Schull |

Department of Agriculture |

Dr. William Stimson |

Department of Public Health |

George Winchester Stone, Sr. |

Supervising Architect's Office |

Ray Palmer Teele |

Department of Agriculture |

James Thurman, Sr. |

Government Accounting Office |

Racial Restrictions

Early deeds for property on Cummings Lane contained a racial restriction, sometimes called a "racial covenant." For example, the deed for 3502 Cummings Lane, sold to Ray Palmer Teele and his wife Mary, included this language:

That the property hereby conveyed, either before or after the improvements are made, cannot be sold, rented, leased or otherwise placed in the possession of a colored man or one of the African race.

This restriction did not appear on any subsequent deeds for this particular home, but such restrictions or covenants in property deeds were not uncommon in the early to mid-twentieth century in the United States. It was not until 1948 that they were made illegal by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the case Shelley v. Kraemer. Despite the ruling of the highest court, racially restricted covenants would continue to appear in property deeds for years; their legacy shaped the patterns of racial and ethnic segregation in residential neighborhoods across the nation.

Mr. Martin’s Third Addition, along his other three additions, were recognized as Martin’s Additions to Chevy Chase by the State of Maryland as a special taxing district in 1916, and in 1985, Martin’s Additions was incorporated as a municipality.

Click NEXT to read about some of the first residents of Martin’s new development along Cummings Lane: the William Orme family, who bought Martin’s home in 1908; the George Winchester Stone family, who moved to their home at 3517 Cummings Lane in 1909; and the Ray Palmer Teele family, who purchased land for their new home in 1906.